Jeanne Vicérial: Bespoke Fashion as Art, Science & Innovation

From Costume as a Reflection of Personality to Fashion Close to the Body

From her earliest childhood, French designer Jeanne Vicérial has been endlessly sketching women and their clothing. Born into a family connected to the circus — the innovative Cirque Plume since the 1980s — she was fascinated from the start by costumes and their transformative power. These garments allow wearers to assume roles, express emotions, and embody characters. Circus costumes, with their daring creativity, became a primary source of inspiration for Jeanne, shaping her vision of costume design and fashion innovation.

After earning her baccalauréat, Jeanne moved to Paris to pursue a two-year professional program in costume and bespoke fashion design, at the only public school in France teaching haute couture and custom tailoring techniques. Unlike most private fashion schools, this program gave her comprehensive technical mastery of corsetry and garment construction, laying the foundation for her future work in bespoke fashion and textile design.

The training was demanding, rigorous, and profoundly technical: students were executors, not creators. Imagination had little room to flourish. Yet it was precisely this rigor that Jeanne sought. At costume school, she acquired the science of clothing, strong foundations in pattern-making, and essential craftsmanship skills.

Two years later, Jeanne joined ENSAD to focus on fashion illustration and innovative fashion design. Surprisingly, she was now criticized for an excess of technicality — her imagination constrained by technical training. This duality between discipline and creative freedom shaped her artistic approach. Thanks to these two complementary trainings, Jeanne combined mastery of bespoke tailoring with a deep understanding of industrial textile production standards.

Before ENSAD, Jeanne designed on real bodies. Now, she had to create on depersonalized mannequins, where imagination precedes industrial adjustment. This contrast was a shock for the young, innovative designer, reinforcing her determination to explore clothing as a second skin.

The Clothing Clinic: Between Textile Innovation and the Philosophy of Bespoke

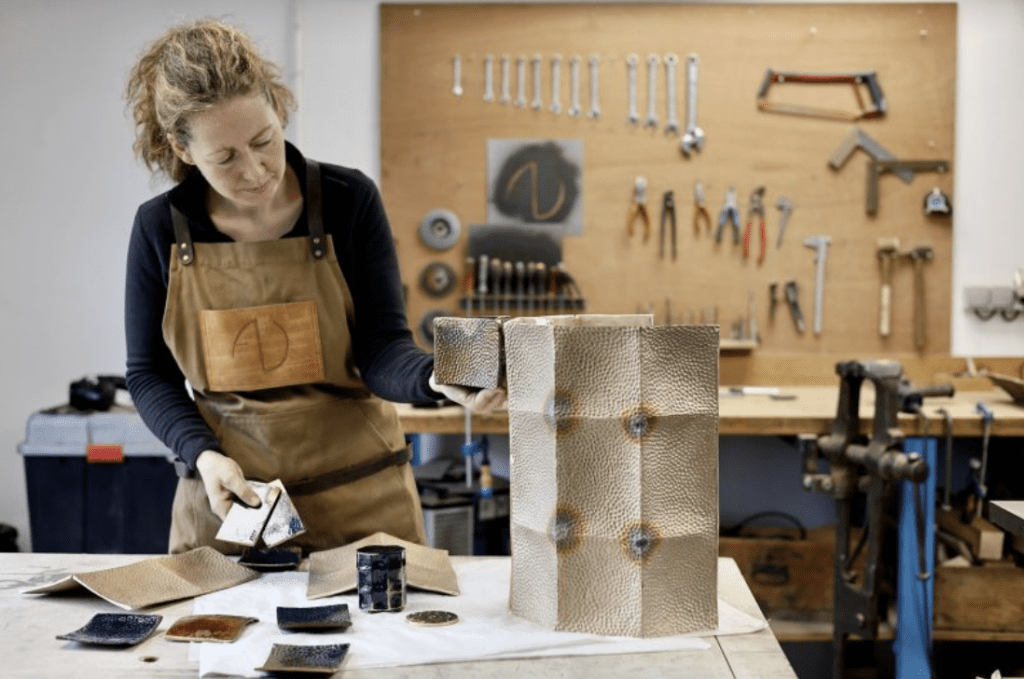

To escape the weight of technical constraints and reclaim creative freedom, Jeanne developed her own method. Gradually, she abandoned fabrics and patterns: thread became her primary medium. Reflection on muscular structure and the desire to explore what lies “beneath the skin” would come later, but already she sought to bring garments closer to the body, creating a true second skin.

In costume and bespoke garment creation, morphology plays a central role. Jeanne studied corset structure in depth and explored pleating techniques. This repetitive, almost meditative practice revealed analogies between the folds of the body and those of clothing.

Jeanne mapped lines and creases, viewing skin as a garment in its own right. Jeanne embraced the concept of repeated lines, cords, and threads, forming a textile topography of the human body.

Her final-year project, The Clothing Clinic, distinguished itself from conventional fashion design, leaning more toward textile philosophy. The concept: multiple laboratory models where custom-made garments could be crafted according to individual measurements. After school, Jeanne attempted to realize this vision, but financial and technical obstacles — common barriers to fashion innovation — quickly emerged.

Learning at Hussein Chalayan: Creation Amid Economic Constraints

Jeanne’s internship with Hussein Chalayan marked a turning point. Presenting her work, she gained access to the designer’s studio. The six-month experience revealed both the rigor of creative fashion design and the harsh realities of the market. When an artist like Chalayan faces financial constraints, creation becomes a daily challenge.

This immersion left a profound impact on Jeanne, illustrating how artistic talent can be limited by economic realities. She collaborated with two exceptionally precise Japanese pattern makers. Her technical knowledge in garment construction enabled her to communicate, learn, and experiment. Together, they completed numerous patterns, deepening her mastery of bespoke fashion techniques.

Participating in runway preparations, Jeanne was fascinated by the tension between imagination and real-world constraints. The experience, exhilarating yet demanding, tested her confidence and shaped her vision of innovative fashion design.

GARDEZ UN OEIL SUR L’ACTUALITÉ, RECEVEZ NOTRE NEWSLETTER

France’s First Scientific Phd in Textiles: Rethinking Bespoke and Innovation

Determined to carve her own path, Jeanne became the first in France to pursue a scientific doctorate in textiles. The Clothing Clinic allowed her to approach bespoke fashion not as collections but as a subject of scientific and textile research. Her goal: accelerate and automate certain couture processes while preserving artisan know-how, achieving in a day what once took a seamstress three months.

In the 1960s, ready-to-wear fashion overtook bespoke tailoring, standardizing bodies and garments. Jeanne sought to create a robotic sewing prototype capable of reintroducing this artisanal practice to contemporary life. Faced with a choice between joining a couture house or pursuing her doctorate — with the financial freedom a scholarship offered — Jeanne chose research, fully dedicating herself to fashion technology innovation.

At École des Mines, she developed the machine from scratch: the first scientific doctorate applied to fashion. Initially skeptical, her supervisors became intrigued by the technical dimension. The mechatronics department, accustomed to diverse projects — from improving Nespresso capsules to textile innovation — welcomed her ideas. Collaborating with inventive engineers proved inspiring.

The project culminated in Jeanne and her five co-authors filing a patent for the textile and mechanical system. The experience also inspired reflections on the human body: once, fashion shaped bodies, then ready-to-wear standardized them, and surgery replaced tailoring. For Jeanne, skin becomes the textile of the 21st century, a living material for innovation and scientific research.

Skin, the New Textile of the 21st Century: Fashion, Science, and Regeneration

Jeanne placed skin at the center of her creative inquiry. She theorized the dialogue between flesh and textile, between body and garment, as both artistic and scientific exploration. Inspired by Li Edelkoort’s notion that “fashion is sick,” she imagined The Clothing Clinic as a laboratory for care and regeneration, restoring clothing’s transformative power.

Reclaiming worn pieces, performing “operations” — lining lifts, material grafts — she gave life back to condemned garments. Gradually, her study of anatomy — muscles, morphology, body structure — informed her innovative textile creations.

The sheer volume of thread necessitated new tools. Jeanne introduced surgical needles and resin injections to secure knots, producing monumental works in the École des Beaux-Arts materials lab. Among her creations: a dress with 466 kilometers of thread and another with 150 kilometers, incorporating upcycled haute couture materials, adding circularity and sustainability. Occasionally, colored threads left marks on her skin, as if she were working with a living textile body.

Exhausted by this labor-intensive work, Jeanne realized automation was necessary to continue exploring garments intimately aligned with the body. Her fascination with anatomy echoes Renaissance masters — Leonardo da Vinci, Michelangelo — dissecting the body to understand form and beauty. Jeanne’s goal: invent 21st-century clothing through meticulous study of flesh, movement, and textile matter.

Overproduction and Its Limits: Rethinking Sustainable Fashion

Jeanne paused her research on robotic bespoke temporarily. She recognized that contemporary fashion stifles creativity: textile overproduction, accelerated collections, and uniform standards suppress innovation.

Yet the pause opened unexpected horizons: sustainable fashion, circular production, and environmental responsibility. Her robotic method operates waste-free, supports local production, and sketches a new urban-centered fashion ecosystem, linking designers and clients directly.

This model revitalizes bespoke craftsmanship, precise and technologically informed. Jeanne envisions a future where custom fashion flourishes in cities, reconnecting designers with clients and restoring the sensory and personal dimension of garments.

While her approach resonates in art and academia, French fashion houses remain largely unresponsive. Internationally, countries like the UK, Finland, and Sweden — pioneers in ethical and sustainable fashion — have embraced the intersection of body, garment, and environment.

Jeanne does not separate fashion, art, and design. For her, these fields enrich each other: fashion interrogates the body, art provides critical distance, and science opens new avenues to reimagine clothing. She redefines creation as a balance of aesthetics, technical mastery, and ecological consciousness.

Art as a Tool to Escape Market Constraints and Explore Creation

During lockdown, Jeanne launched an Instagram blog, exploring color, patterns, and texture. Isolation at the Villa Medici in Rome became a free experimentation lab, outside the commercial constraints of traditional fashion.

Art, broader and less codified than fashion, allowed her to observe the system while remaining independent. Jeanne reinvented forms, materials, and volumes, extending her reflection on bespoke sewing and innovative textile design.

Her online presence attracted artists, designers, costume makers, and fans of ethical fashion. This community supported Jeanne’s conceptual and poetic approach, at the intersection of contemporary art, textile design, and applied fashion science.

Through her creations, Jeanne continues a quest: harmonizing art and technique, material and idea, inspiration and innovation. For her, creating is thinking, and thinking about fashion restores its soul and meaning, beyond trends and industrial cycles.

- Jeanne Vicérial: Bespoke Fashion as Art, Science & Innovation

- Sophie Théodose, Parchment Ciseleur, at the Carrousel du Louvre

- Irina Bokova: Artisanal Craftsmanship in the Service of Contemporary Creativity

- Elliott Barnes: The Elegance of Detail and the Poetry of Materials

- Sophie Théodose and Parchment: Reviving an Ancient Art

RECEVEZ NOTRE NEWSLETTER